On December 16 the

Calendar of Cashel, an eleventh-century source sadly no no longer extant, records a feast attributed by some of the nineteenth-century scholars of the saints to Saint Dabheoc of Lough Derg, the County Donegal site of the Saint Patrick's Purgatory pilgrimage. Saint Dabheoc has two feasts preserved in the Irish martyrologies, one at

January 1 and one at

July 24. None of them mention a third feast day at December 16 and it seems, from what the Ordnance Survey scholar John O'Donovan recorded when he visited Saints' Island in 1835, that the source of today's feast is the seventeenth-century hagiologist, Friar John Colgan, who had access to the now lost

Calendar of Cashel:

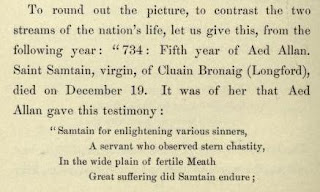

Colgan,.. speaking of Daveog, the patron, .. says: St. Dabeocus is held in the

greatest veneration to the present day, and his festivity is observed

three days in every year, according to our Festilogies, viz., on the 1st

of January, 24th of July, and 16th of December. So Marian Gorman,

Cathal Maguire and the Martyrologies of Tallaght and Donegal. But the

Calendar of Cashel places his festival day only on the 16th of December.

Michael Herity, ed. Ordnance Survey Letters Donegal- Letters Containing

Information Relative to the Antiquities of the County of Donegal

Collected During the Progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1835 (Four

Masters Press, Dublin, 2000), 122-123.

Since the December feast is missing from the earliest martyrologies as well as from the 1630 Martyrology of Donegal (where we might have expected to find it), I wondered if it was possible that we were dealing with a case of mistaken identity here. That suspicion was strengthened when I noted that Professor Ó Riain's Dictionary of Irish Saints discusses another Ulster saint, Mobheóg of Artraige, at December 16. Here we are back to the familiar problem of the many different forms that the names of Irish saints can take, for Dabheoc or Dobheóg is sometimes known as Beoán, Beóg and Mobheóg. It therefore seems possible that the feast in the Calendar of Cashel, attributed by Father Colgan to Dabheoc of Lough Derg, was actually the feast of Mobheóg of Artraige observed in Wexford on December 16. But although I am not convinced that today is a feast of Saint Dabheoc of Lough Derg I am nevertheless delighted to offer another reminder of his career as he is a saint to whom I feel a personal connection. I have taken part in the pilgimage at Lough Derg three times and on my first all-night vigil I was sorely tempted to give up when the going got tough. Instead I made my way to the side altar of the basilica where the statue of Saint Dabheoc stands and asked for his help to complete the rest of the vigil. I have asked for his intercession ever since and feel he is one of many Irish saints who deserves to be better known.

The account below of Saint Dabheoc and his island home has been taken from Chapter Five of Father Daniel O'Connor's 1879 guide to Lough Derg:

Oilean-na-naomh

About two miles north of Station Island lies

Saints' Island, anciently called Oilean-na-naomh, and more anciently

still, St. Dabheoc's Island [This name, "Dabheoc," is usually pronounced as if written Davoc.]. In pre-Reformation times there stood on

Saints' Island a venerable convent of Augustinians; and, at least down

to the year 1497, this island would appear to have been the place of

pilgrimage. The island is like a ring in form, and rises on all sides in

gentle acclivity from the lake, its highest elevation being about forty

feet above the level of the lake.

Saints'

Island bears evident traces of agriculture, and of having been turned

to profitable account in the days when the Canons Regular of St.

Augustine were denizens of the place. The soil of the island is rank and

loamy, and seems to have partaken of the ruin which has visited with

such destruction its holy cloisters and churches. It is quite overgrown

with coarse grass, with ferns and rushes; and in some parts of it a

stunted covering of heather indicates that it has, to some extent,

returned to its original state of wildness. The ruins of the sacred

enclosures, monastery, churches and cemetery, are overgrown with

luxuriant weeds. The island has very few trees or shrubs, if we except

some slender trees of mountain ash, and some whitethorn bushes, which

are really worth observing, as they are hoar with antiquity. These

bushes are sparsely scattered over the island, but at its eastern

extremity a dense cluster of them overshadows the debris of the

buildings; and, judging from the gray, dank moss adhering to their

branches, they appear to date from the time these buildings were

demolished.

On the southern slope of the island were situated the convent gardens, as we may plainly infer from the

enclosures, as well as from the superior fertility of the soil. During the winter season these gardens present a more marked contrast for their verdure; and herbs and flowers are known to grow here, which are not found elsewhere through these islands and mountains.

The eastern half of the island was laid out in fields, as the remains of the earthen fences or enclosures denote. These fences are inhabited by a numerous colony of rabbits, of different colours, brown, white and black, that skip about in every direction, and in a variety of ways contribute their own little best "to lend enchantment to the scene."

The western half of the island appears to have been used as a "common" for pasture, as it is not intersected by fences, though here also the furrowed surface presents indications of its having yielded to the beneficent sway of the spade and ploughshare.The grass and hay grown on Saints' Island are said to be so rank and unsavoury as to be very noxious to cattle. Formerly, I have been informed, cattle and sheep were put to pasture on it, till the mortality which set in amongst them awakened their owners to the dangers of the situation. And thus, fortunately, the sacred precincts and ruins on the island are no longer trampled upon, dishonoured and profaned by the beasts of the field, which in other places have occasioned such injury to the ancient monuments of our country.

In the early ages of the faith in Ireland there appears to have prevailed a custom, borrowed from the pagan period, of erecting a circular earthen fort or enclosure convenient to, or around the religious houses. Thus, in Father O'Hanlon's Life of St. Fanchea, we read of her brother, St. Endeus, having with his own hands raised round his sister's nunnery, at Rossory, a large múr, or earthwork, strengthened by deep circular fosses, the remains of which are still to be seen. And Mr. Wakeman, in his Antiquities of Devenish, says that nearly all the primitive church sites in Fermanagh bear traces of such circumvallations. The writer of the present subject, from his own personal observation of some of

these sites, can fully endorse Mr. Wakeman's statement. Near the Abbey of Devenish stood a strongly-fortified rath, remains of which are still evident. The same may be said of Rossory, Inniskeen, &c. Outside Fermanagh the same custom also prevailed. At Clogher and Clones religious houses were founded, for economy sake, near forts, of which we have sufficient evidence for saying that they were erected during the pre-Christian period of our country.

On Saints' Island, also, the visitor will perceive a circular earthwork of this class, on the very summit of the island, and to the west of the monastery and cemetery. The diameter of this enclosure measures about twenty yards. A part of this circular earthwork has been intersected by the cemetery, which lies to the east of it; but as much of it, fortunately, still remains as to leave no doubt whatever as to the character and object of this primitive work. It seems strange, indeed, that this interesting object escaped

the notice of the Ordnance Survey party, and even of O'Donovan himself, who visited the island on the 28th of October, 1835. It is much to be regretted that O'Donovan did not devote more of his time and attention to this locality; as, with his rare knowledge, much that is now hopelessly lost might have been brought to light. He came, as we said, on the 28th of October, and on Hallow-Eve following he wrote, from Ballyshannon, an account of his visit to the lake, having derived, as he jocosely states, no benefit from his turas save a severe cold.

Within this fort on Saints' Island, or, at any rate, in the cemetery adjoining, it is not too much of conjecture to say that the monastery founded here by St. Dabheoc, in the days of St. Patrick, stood; and that here his order flourished till the time of the Danish invasion....

...There is an air of loneliness and desolation about Saints' Island, which is truly affecting. Silence, still as death, reigns round these holy precincts, where once the prayer of the pilgrim, the pious chant of the monks, 'mid ceremony and sacrifice, resounded. Of this island we may repeat with truth what was said of "Arran of the Saints," that the living God alone knows the number of holy persons who here await their final resurrection.

Standing on this holy island, where stood the monastery of St. Dabheoc, where stood the sanctuary of Saint Patrick's Purgatory, which during the middle ages became'the most famous shrine of penance and purification in Western Europe' the following sweet lines recur to memory: —

"God of this Irish isle,

Sacred and old,

Bright in the morning smile

Is the lake's fold;

Here where thy saints have trod,

Here where they prayed,

Hear me, O saving God!

May I be saved!"

Rev. Daniel O’Connor, Lough Derg and Its Pilgrimages (Dublin, 1879), 26-31.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2022. All rights reserved.