May 20 is the commemoration of a County Donegal saint, Conall (Connell, Conald) of Iniscaoil. I introduced this saint

here at which time I mentioned that a second saint with a similar name is commemorated on May 22. There is a post on the second Saint Conall

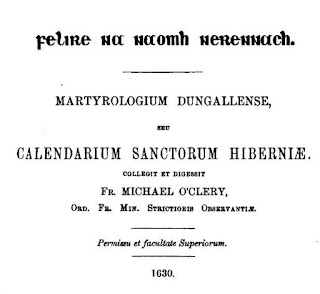

here. There may well be some confusion regarding the date of the feastday, although the 17th-century hagiologist, Father John Colgan, believed he was dealing with two distinct individuals. Saint Conall was said to have enjoyed the friendship of the poet saint Dallan Forgaill, best known for his hymn in praise of Saint Columcille, both were members of the Columban family. In the paper 'Iniskeel' below, abridged from the

Irish Ecclesiastical Record, the author writes of Saint Conall's island home and of the

Turas or stations performed in his honour. Unlike some other writers of the period, he is at pains to defend these traditional practices from the charge of superstition, and as a Catholic writer he is naturally delighted by the traditions linking this Donegal saint with Rome. In his presentation of a romantic view of the island home of Saint Conall, the writer is very much in tune with the spirit of his age. The imagery of remote, windswept landscapes where the mind could not help but turn to God played, and indeed still plays, an important role in the portrayal of the 'Celtic Church' and its saints.

INNISKEEL.

"Dim in the pallid moonlight stood,

Crumbling to slow decay, the remnant of that pile,

Within which dwelt so many saints erewhile

In loving brotherhood."

OFF the coast of Western Donegal, in the district anciently known as Tir-Ainmirech, but called Boylagh, since the thirteenth century, lies the holy island of Connell Coel....The island has a sacred interest in the present and the past with a long, if broken, history to commemorate its former greatness. It is still the seat of a much frequented pilgrimage in honour of St. Connell, one of the most remarkable of Ireland's early saints. It contains his church and cell; and in it repose his sacred remains in the grave that had first closed over the body of his illustrious friend, St. Dallan.

The "station" may be performed at any time. But the solemn season lasts from the 20th of May, St. Connell's day, to the 12th of September. Besides the founder's well, there is another sacred to the Blessed Virgin. Fixed prayers are devoutly said at each, as also in going round the penitential piles, of which there are several, formed as a rule of small sea-stones which are kept together by the self-mortifying attention of the pilgrims. A number of decades repeated in walking round the old ruins and before the altar of St. Connell's Church bring the Turas to a close.

The devotion and faith of the crowds who throng to Inniskeel during the Station season recall the memory of the first believers in Christianity. They possess the genuine spirit of Gospel Christians, and it would be strange indeed looking to the beneficence of God's providence towards simple, faithful souls, if prayers offered up with such fervour and commended by such powerful patronage, did not bring down, on those devout pilgrims the choicest blessings of heaven. They speak to their Saviour in earnest communion of heart, believing firmly that He is the physician of physicians for soul and body. Is it then unreasonable to think that for these meek confiding ones Christ in view of Connell's merits allotted curative properties to the saint's well? Their faith, their prayers, and the blessing of heaven on the spot do indeed work wonders. Nor need going round the piles a fixed number of times, raising at intervals the position of some low-placed pebble, or moving larger stones round the head and waist, force up the idea of superstitious observance.

If St. Connell or any one of his saintly followers wished to found a penitential and supplicatory course of exercises, what more proper than that their ritual should be minutely fixed and accurately handed down? Now this is the feeling that sways these crowds of pilgrims from age to age. Their faith is simple and their hope unbounded. Flourish such faith and hope! They give as just a notion of God's warm providence as the acutest reasoning of philosophy.

There seems to be no ground for questioning the popular belief that St. Connell founded the buildings which still remain. At the same time substantial parts were certainly rebuilt at a later period. Both church and cell are situated on a beautiful slope of the south-eastern side of the island. The orientation of the church seems perfect. The other edifice which stands a few paces further east points in the same direction. The ground plan of both buildings is rectangular, the former measuring fifty feet by twenty, the latter something less in breadth, but almost the same in length. The church retains its gables, windows, and doors, in an state of fair preservation; but one of its sidewalls is almost completely broken down for some yards. The altar table, of substantial flags, has retained its hold with magnificent tenacity. The cell or monastery is in a still more ruined condition. Apparently it was never so high as the church, and at present gables, from a little above the square, serve but to block the doors and narrow windows or fill in gaps in the lower masonry of its walls. Neither building can lay claim to exceptional beauty of architecture, but they are fairly large in size, neatly and well built, and above all charmingly placed in situation.

On this delightful ground with the waves expiring gently at his feet or rolling in fury on "the Ridge" beyond, St. Connell raised each morning his pensive soul from thoughts of nature's beauteous handiwork to contemplate the great, Creator by whose almighty word it had all been fashioned before time for man began. A glance northwards enhanced the view. It should have swept over kingly Errigal, and rest on Aranmore or the chainless waves of the sky-meeting ocean. What a home for meditation this peaceful isle with such giant surroundings by land and sea! Assuredly no island recluse can be an atheist, can fail of being an intense believer. With the impress of divine intelligence above him and around him, with a voice in the heaving billows or rushing sea-wind, if he have ethical uprightness of intellect and will to grasp the significance of the scene, no man could escape the all-pervading sense of God's presence, no man could here live the life of a hopeforsaken infidel. Neither the din of cities, nor social strife, nor crowded brick and mortar intervene to shut out reason's strong lesson or the light of divine faith. The island saint is a true philosopher; he must be religious to the core.

Such was Connell, founder of Inniskeel, and such was Dallan its frequent visitant. Colgan has left us several particulars of the latter saint. His notes on St. Connell are only incidental. The Christian name of Inniskeel's patron is variously spelled in Irish as in English, the form Conald being supported by some ancient authorities, whilst Conall, Connall or Connell approaches much nearer the pronunciation (Cuinell) common in Boylagh. In like manner his second name is written Caol, Caoil, Cael, Coel or Ceol. Mac Cole is still a family name on the mainland. The local Irish pronunciation, however, sounds like Caol (slender), and hence some have thought the island derived its name from the needle-like appearance it presents from certain points of view along the coast. But more probably it came from Connell's father, for to distinguish the saint from a famous Umorian chief, who bore his double appellation, he is described by our annalists as the son of Ceolman. Thus in Latin he is said to be filius Ceolmani or filius Manii Coelii.

The year of St. Connell's birth is not known with exactness. He died about 590 and had therefore been contemporary with a host of Irish saints. Sprung from the Cinel Conall, being the fourth in descent from Conall Gulban, he was a near relative of St. Colomba. His name is mentioned in several of our ancient records. It is linked for ever with the famous Cain Domnaigh, a law forbidding servile works on Sunday. The prohibition ran from Vespers on Saturday evening to Monday morning and should delight the heart of a Sabbatarian by its exacting observance, did it not in other respects so unmistakably savour of Catholic practice. In the Yellow Book of Lecan the Cain is prefaced by a statement of its being brought from Rome by St. Connell, on an occasion of a pilgrimage made by him to the Eternal City. The metrical version contained in a manuscript copy of the ancient laws (in Cod. Clarend), says it was the "Comarb of Peter and Paul" who first found and promulgated the document. St. Connell is not credited in either account with its authorship. Nay, O'Curry thinks he was a hundred years in his grave before a knowledge of it became general in Ireland. Be this as it may our chroniclers make two notable statements in regard to it. They say it was written by the hand of God in heaven and placed on the altar of St. Peter, and secondly that it was brought from Rome by St. Connell. Now, however we may be inclined to explain away either or both these statements, there is no mistaking the avowal of respect they imply for Roman authority, nor any serious reason for calling the pilgrimage itself into question. And see the faith of our fathers shining through the old Irish ordinance. Though the law in its severity forbids journeying on a Sunday, yet

" A priest may journey on a Sunday,

To attend a person about to die,

To give him the body of Christ the chaste,

If he be expected to expire before morning."

The Cain Domnaigh was never enacted by the states or Councils of Erin. That it was believed to have been brought from Rome sufficed to spread its sway.

It is now time to say something of St. Connell's famous friend Dallan Forgail. Euchodius is the Latin form given by Colgan for his original name. The better known appellation of Dallan is obviously derived from dall, blind; for at an early stage in his career he lost the use of his eyes. Notwithstanding this dismal fate he became the most eminent man of letters in Ireland, at a time when the paths of scholarship were eagerly pursued by a host of able men. He was antiquary, philosopher, rhetorician, and poet all in one. He was the literary chief, the file laureate of Erin in his day. A saint's life and a martyr's death crown the glory of his fame.

He was born, as Colgan tells us, in Teallaeh Eatbach, which we take to be Tullyhaw in Cavan. Removed by only a few degrees of descent from Colla, King of Ireland, St. Maidoc, of the same lineage, was his cousin. From his mother, Forchella, he received the second name, Forgail, which we sometimes find added in the old writers. Nothing that parental care could accomplish was left undone to perfect his education in sacred and secular subjects. From an early date he took to the antiquarian lore of his country as a special study. It was in this department, so indispensable for an Irish scholar of the sixth century, that he first attained an eminent place. Not unlikely his research into ancient records had something to do with the difficulty of the style in which he wrote. It appeared archaic even to experts who lived centuries before Colgan wrote; and we are told by this author how in the schools of Irish antiquities it was usual to expound Dallan's compositions by adding long commentaries on these rare specimens of the old Celtic tongue.

The Amhra Coluim Cille or written panegyric on Columbkille was his best known work. When the famous assembly at Drumceat was breaking up, just after Columba had succeeded in directing its proceedings to such happy issue, Dallan came forward and presented the saint with a poem written in eulogy of his merits. A part of the composition was thereupon recited ; but only a part. For, as the event is told by Colgan, a slight feeling of vain-glory brought the demons in whirling crowds above Columba's head, before the astonished gaze of St. Baithen, his disciple and attendant. No sooner did the person principally concerned in this wonderful occurrence perceive the terrible sign than he was struck with deep compunction, and immediately stopped the recital. No entreaty ever after could induce him to allow the publication of the panegyric during his life. But by unceasing effort Dallan obtained the saint's permission to write a eulogy of him in case of survivorship. An angel, we are told, brought the news of Columba's death to St. Dallan, who forthwith composed his famous Amhra Coluim Cille, embodying in all probability, much of his former panegyric.

As soon as the learned work was completed Dallan recovered his sight, and received a promise that anyone who would piously recite the composition from memory should obtain a happy death. This promise was liable to abuse in two opposite ways. The wicked might be tempted to look upon the recital of the eulogy as an easy substitute for a good life. The good, from seeing this interpretation carried into practice, might naturally be inclined to turn away in disgust from all use of the privilege. In point of fact both these errors began to show themselves, and were sure to grow, did not a miraculous event occur to put the promise on a proper basis. A cleric of abandoned life took to committing the rule as a more comfortable way to heaven than the path of penance. But, after learning one half, no effort would avail for further progress. So, as he still wanted to put off, or rather get rid of the day of reckoning, he made a vow, and in fulfilment of it went to Columba's tomb, whereat he spent a whole night in fast and vigil. When morning dawned his prayer had been heard. He could recite the second part of the poem word for word. But to his utter confusion not a trace of the lines he had known so well before remained on his memory. What happened him in the end we are not told. Let us hope he applied the obvious lesson his story preaches. As Colgan says, it not merely showed that a true conversion of heart must accompany the pious repetition from memory of Columba's praises, if eternal life is to be the reward. In this particular instance the value of the promise was clearly conveyed. The person's perverse intention was visibly punished by his being afflicted with inability to fulfil an indispensable condition of the privilege. He could not even commit the words.

St. Dallan composed another funeral oration in praise of St. Senan, Bishop of Iniscattery. It was prized both for its richness of ancient diction, and for the valuable property of preserving from blindness those who recited it with devotion. He composed a third Panegyric on St. Connell Coel for whom he entertained a most enthusiastic esteem. Colgan, who says he possessed copies of the two former compositions, states that he knew not whether that on the Abbot of Inniskeel was then extant. All three, unfortunately, are now gone.

Dallan had often besought in prayer that he and St. Connell might share the same grave. The favour came to be enjoyed in a manner at once saintly and tragic. He had been a frequent visitor at the island monastery, and the last time he came, a band of pirates landing from the neighbouring port, burst into the sacred building, as he was betaking himself, after the spiritual exercises, to the repose of the guest-room. These fierce sea-rovers, who in all probability were pagans, from more northern coasts, plundered ruthlessly on all sides, and brought their deeds of sacrilege to a close by cutting off the old man's head and casting it into the ocean. The abbot, who contrived to escape, on hearing that his dear friend had fallen a victim to the murderers, rushed to the spot where ho had been slain, but only to find the headless trunk of what had been St. Dallan's body.

With tears and prayers he at once appealed to God, beseeching Him to reveal where the head of his martyred friend had been cast. The petition of one so favoured of heaven was granted. He saw it rise and fall on the waves at a distance and then move to the shore. He took it up with reverent care and placed it in its proper place on the body, when, lo! to his grateful delight, he found the parts adhere as firmly as if the pirate's cutlass had never severed them. St. Dallan's remains were then buried under the church walls with all the honour such earnest and mutual esteem was sure to prompt. This occurred about the year 594. Before the century closed St. Connell's body was laid in the same grave. Thus was St. Dallan's life-long wish gratified at last. No wonder the spot should be, in Colgan's words, the scene of daily miracles.

St. Dallan's Feast occurs on the 29th January. His memory survived in the veneration of several other churches throughout Ulster.

A very remarkable relic of St. Connell remained in the neighbourhood of Ardara until 1844. It was the saint's bell, called Bearnan Chonaill. It was purchased in 1835 by Major Nesbitt of Woodhill, for £6, from Connell O'Breslen of Glengesh, whom O'Donovan calls the senior of his name. The O'Breslens, who had been erenaghs of Inniskeel, claimed St. Connell as of their family, and hence the inheritance. Since 1844 when Major Nesbitt died, it has entirely disappeared and fears are entertained that in the succession of owners it may have been destroyed beyond hope of repair. Fortunately it had been previously seen and described by eminent antiquarians. We cannot convey a better idea of its appearance than by transcribing the following paragraph from Cardinal Moran's Monasticon Hibernicum. It is almost an exact transcript from one of O' Donovan's Letters.

"O'Donovan says it was enclosed in a kind of frame or case which had never been opened. Engraved on it with great artistic skill was the crucifixion, the two Marys, St. John, and another figure, and over it in silver were two other figures of the Archangel Michael, one on each side of our Lord, who was represented in the act of rising from the tomb. There is a long inscription in Gothic or black letters, all of which are effaced by constant polishing, except the words Mahon O'Meehan, the name, probably, of the engraver. There are two large precious stones inserted, one on each side of the crucifixion, and a brass chain suspended from one side of the bell."

Frequent mention is made of Inniskeel by our ancient writers. Its exposed position not infrequently tempted the spoiler. Thus under the year 619 in the Four Masters its demolition by Failbhe Flann Fidhbhadh is recorded. This war-like chief was killed to avenge Doir, son of Aedh Allan. Failbe's mother said, lamenting him

" Twas the mortal wounding of a noble,

Not the demolition of Inniskeel,

For which the shouts of triumph were exultingly

Raised around the head of Failbe Flann Fidhbhadh."

...The island of St. Connell lies at present outside the parish of Inniskeel. Half a century ago itself and the adjoining districts were ceded to Ardara in exchange for certain townlands lying near Glenties. So the people of both parishes look to it with equal pride, and visit it with equal reverence.

We feel sure that the lesson its great saint teaches as well as the benediction they obtain, will stand the children of Boylagh in good stead as the ages roll on. This said, we have completed a little vacation tribute of homage and gratitude, long since intended, to St. Connell and St. Dallan.

PATRICK O'DONNELL.

Irish Ecclesiastical Record, Vol. 8 (1887), 781-794.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.