Pages

- Home

- Irish Saints of January

- Irish Saints of February

- Irish Saints of March

- Irish Saints of April

- Irish Saints of May

- Irish Saints of June

- Irish Saints of July

- Irish Saints of August

- Irish Saints of September

- Irish Saints of October

- Irish Saints of November

- Irish Saints of December

- Irish Saints' Names for Children

- Mass of All Saints of Ireland (1962 Missal)

- Litany of All Saints of Ireland (1921)

- Lent with the Irish Saints

- Notes on Homonymous Saints

- Notes on the Life of Saint Brendan

Wednesday 28 January 2015

Saint Acobran of Kilrush, January 28

January 28 is the feast of Saint Acobran of Kilrush, about whom not a great deal appears to be known. We have already met this saint, for in a post on a trio of saintly brothers commemorated on 28 November, I mentioned the contention of the English writer, Sabine Baring-Gould, that one of these brothers, also called Acobran, was to be identified with today's saint. If our Acobran did indeed go off to Cornwall and later on to France as Baring-Gould claims, Canon O'Hanlon knows nothing of it, and it would not be like the good Canon to fail to claim such a career for an otherwise obscure Irish saint. On the contrary, in the Lives of the Irish Saints Acobran is depicted as a shadowy figure whose very location is the subject of doubt, with the Martyrology of Donegal initially identifying him with Kilrush, County Clare but then suggesting in the table appended to the Martyrology that this particular Kilrush is to be found in County Kildare. In the late 1830s when O'Donovan and his co-workers were carrying out their Ordnance Survey work in the parish of Kilrush, County Clare a letter noted 'According to the Irish Calendar the Saints Mellan and Occobran were venerated at Cill Rois in the Termon of Inis Cathaigh on the 28th of January, but neither of them is now remembered in the Parish'. It may be that the cult of the most famous saint of Inis Cathaigh, Saint Senan, overshadowed and eventually displaced that of Saint Acobran. Canon O'Hanlon, as he often does when there is not much to say about a saint, goes into a description of church ruins associated with Saint Senan, but below are the essentials of what he has to tell us of Saint Acobran:

St. Acobran of Kilrush, Probably in the County of Clare.

...Without any other distinction, he is mentioned in the Martyrology of Tallagh, at the 28th of January, But we are not left in doubt regarding his locality, if we depend on the succeeding statement. According to the Martyrology of Donegal, we find Accobhran, of Cill-Ruis, in the Termon of Inis-Cathaigh, as having a festival celebrated on this day. In a table postfixed to this Martyrology, his place is thought to have been Kilrush, in the county of Kildare. He is said to have been otherwise called Occobhran, whence Ocobrus, Ocoras [Desiderius). The place usually designated for this saint is the present Kilrush, a parish in the barony of Moyarta and county of Clare. The present saint, to whatever place he belonged, appears to have lived in or before the eighth century. This is proved from the "Feilire" of St. Aengus the Culdee. With its English translation, Professor O'Looney has furnished the following stanza from the Leabhar Breac copy in the R. I. A.

G. u. kl. With Acobran we celebrate

The passion of eight noble virgins;

They gained a triumph of righteousness,

The great Miserian host.

These latter seem to have been martyrs in Africa, and to have been part of a band, commemorated in St. Jerome's ancient Martyrology....

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Tuesday 27 January 2015

Saint Cróine, January 27

January 27 is the feastday of an early female saint, Cróine, one of many Irish saints to have been recorded on the Irish calendars, but who has left no Vita to give further details of her life. As Canon O'Hanlon explains, there is even no certainty as to the locality in which she may have flourished, the Martyrology of Tallaght identifying her with Inuse Lochacrone which may suggest a County Sligo location, and the 19th-century scholar John O'Donovan placing her at Kilcroney, County Wicklow. The latest work on the Irish saints, Pádraig Ó Riain's 2011 Dictionary of Irish Saints, places her instead at the County Carlow location of Ardnehue (Ceall Inghean nAodha) and sees her as one of three daughters of Aodh. Ó Riain acknowledges the confusion of this holy lady with others of the same name, including Cróine of Inis Cróine, who may be one of a number of possible doubles.

St. Croine, Virgin, of Kill-Crony, in the County of Wicklow, or at Inishcrone, County of Sligo.

A festival in honour of Croni of Inuse Lochacrone is entered in the Martyrology of Tallagh, at the 27th of January. The locality named is possibly identical with the present Inishcrone, near the River Moy, in Tireragh barony, county of Sligo. A strong castle of Eiscir-Abhann, stood here. Inishcrone town, with the ruined church and graveyard, is in the parish of Kilglass, and near the rocky shore, at Killala Bay. Again, there was a Cill-Cruain, now Kilcrone, an old church, giving name to a townland and parish in the barony of Ballymoe, in the county of Galway. We find that Croine, virgin, of Cill Croine, is recorded, likewise, in the Martyrology of Donegal, on this day. She is of the race of Máine, son of Niall. Her place has been identified with Kill-crony, in the county of Wicklow, and as giving no name to a modern parochial district, it may have been denominated from the establishment of a cell or nunnery here, by the present saint, while possibly clerical ministrations had been supplied by the religious community or pastor, living at Kilmacanoge, in remote times. More we cannot glean regarding this holy woman yet, we may conjecture, she must have flourished at a very early period.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Sunday 25 January 2015

The Meeting of Paul and Brendan

When the saints are mentioned in the Irish sources, it is primarily as the exemplars and prototypes of the eremitic life, and hence of monasticism. Thus the Life of St Columcille in the Book of Lismore gives the monastic life as the first way by which men are summoned to knowledge of God; and the monastic vocation is described as ‘the urging and kindling of men by the divine grace to serve the Lord after the manner of Paul, and of Anthony the monk, and of the other faithful monks who used to serve God in Egypt.’ In the Stowe Missal, likewise, Paul and Anthony are named as the exemplars of the eremitic life.Ó Carragáin goes on to contrast this appreciation for the pair among the Irish with the attitude of the Anglo-Saxons:

Saints Paul and Anthony seem to have been popular in Celtic lands because the Irish, and their Scottish settlements, revered them as prototypes of monasticism. For Anglo-Saxon monks, St Benedict of Nursia would usually have occupied this position of pre-eminent reverence. Wandering anchorites who met, however providentially, in the desert could not be honoured with unqualified reverence by communities founded on a vow of ‘stabilitas loci’. For later Anglo-Saxon homilists, ‘instability of place and wandering from place to place’ was a product of sleacnes (sloth), one of the eight capital sins.Saint Brendan finds ‘Paul the Spiritual Hermit’ living on a small circular-shaped island. For thirty years he has been fed by an otter, which brings him a fish and firewood for cooking every three days. When Saint Brendan arrives, however, the hermit has moved to occupy ‘two caves, the entrance of one facing the entrance of the other, on the side of the island facing east’. The otter no longer brings food, as the hermit now subsists entirely on the waters of ‘ a miniscule spring, round like a plate, flowing from the rock before the entrance to the cave…when this spring overflowed, the rock immediately absorbed the water’.

Ó Carragáin comments:

We clearly have here, not another version of the life of Saint Paul the First Hermit, but a different figure, set in a new landscape which develops in an original way the themes of the desert scene in the Vita Sancti Pauli. This Irish Spiritual Hermit inhabits a landscape which is entirely symbolic; and its symbolism is primarily eucharistic. We have already seen the eucharistic significance of the symbol ‘fish’. The eucharistic significance of water that is miraculously given from a rock is equally central to Christian tradition. St. Paul’s gloss on the ‘wandering rock’ which accompanied the Israelites in the desert [1 Corinthians 10:1-4] is relevant to the island-rock which sustains this Spiritual Hermit. [In a footnote the author also says: in his use of the spring as an image for Christ’s giving of himself as drink, the author of the Navigatio is probably thinking also of such texts such as John 7:37-8 and John 19:34.]The writer argues that the point of all this eucharistic imagery is revealed at the end of the chapter when the hermit gives Brendan and his crew a supply of water from the spring to act as the sole sustenance for their next forty-day voyage. The symbolism is further brought into focus when we note that Saint Brendan’s voyage comes to an end on Holy Saturday and thus the meeting with the hermit must have taken place on or close to the first Sunday of Lent.

Ó Carragáin has many more interesting points to make on the meeting of Paul and Brendan, but for now I will conclude with his tribute to the writer of the Navigatio and his use of the Vita Sancti Pauli:

The wit of the Navigatio depends on an unobtrusive mastery of paradox: the author demonstrates that the famous scene of the meeting of Saints Paul and Anthony can be re-enacted, not with bread alone, but with other images of how man is fed by God’s word. He transforms the famous scene in the Vita in such a way as to suggest that fasting gives sustenance to the spirit, and that the contemplative vocation (the vita theorica) can provide fulfillment even on stony ground.

The details of chapter xxvi of the Navigatio can thus be seen to interact, as it were in a form of counterpoint, with the corresponding details in the Vita Sancti Pauli; and it can be seen that to appreciate the sophisticated virtuosity of the Navigatio it is necessary to have some recollection of the Vita. No doubt the author of the Navigatio felt he could depend on his monastic readership for such a recollection. In the scene in which St Brendan meets St Paul the Spiritual Hermit, the author clearly was just as preoccupied with the eucharistic themes of the recognition of and union with Christ as Jerome had been in the Vita Sancti Pauli. The Navigatio therefore provides strong confirmatory evidence that for Irish audiences the meeting of St Paul and St Anthony had primarily a eucharistic significance. The way in which the Spiritual Hermit is made to greet St Brendan with the verse ‘ecce quam bonum et quam iocundum habitare fratres in unum’ suggests that the author of the Navigatio is making explicit another theme which he saw Jerome’s account of the meeting of Paul and Anthony to imply: that friendship and community could, miraculously, be found even in the desert. This theme may also be relevant to the ‘Paul and Anthony’ panels on the high crosses, those monastic scenes of courteous friendship which the sculptors consistently placed in eucharistic contexts.

Éamonn Ó Carragáin ‘The Meeting of Saint Paul and Saint Anthony: visual uses of a Eucharistic motif’ in G. Mac Niocaill and P.F. Wallace, eds. Keimelia – studies in medieval archaeology and history in memory of Tom Delaney (Galway University Press, 1988), 1-58.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Saturday 24 January 2015

A Seminar on the Shrine of Saint Manchan

24 January is the feast of Saint Manchan of Lemanaghan, a saint whose memory still flourishes today and whose name is most famously associated with the splendid shine preserved for veneration at the parish church in Boher, County Offaly. Below is an account of a 2003 Irish Studies Seminar held at Columbia University when Professor Karen Overbey spoke on the topic of Saint Manchan's shrine. She helps to place this relic into an historical context, particularly interesting is the political dimension and the relationship between the monastery of Lemanghan and its much more famous neighbour at Clonmacnoise.

Speaker: Professor Karen Overbey

Title: “Holy Ground: Politics, Patronage, and Iconography of St Manchan’s Shrine”

Prof. Overbey presented a talk with slides. St Manchan’s Shrine, which is kept in the parish church in Boher, Co. Offaly, very near to the site of St Manchan’s medieval monastry at Lemanaghan, is the largest surviving Irish reliquary—the richly decorated, containers for the remains of a saint. Holy relics, and even their reliquaries, were the prized possessions of medieval monasteries; the presence of the saint guaranteed the sanctity of the monastic space, and allowed a connection between the earthly inhabitants and the world of the divine.

Many of the shrines features mark it as exceptional. Professor Overbey noted, however, that the oddities of the shrine—its size, its form, its decoration, its figures—rather than spurring exploration, has spurred categorization. Prof. Overbey suggested that through a re-evaluation of the literary, folkloric, political and geographic contexts, St Manchan’s shrine would become less “bewildering.”

St Manchan’s shrine was clearly intended to be carried and displayed—at each junction of base and leg there is a stout brass ring through which a pole could be slid, allowing the shrine to be hoisted and carried. St Manchan’s shrine is approximately five times larger than the tomb-shaped shrines, and its display, on the shoulders of four monks presumably in a procession—would have been public and communal. The small tomb-shaped shrines in contrast were designed to be carried individually, and perhaps somewhat privately or protectively, as on a journey.

St Manchan himself was a founder of monastry approximately twelve miles east of the community of Clonmacnois; the site was called Lemanaghan. Despite its small size, Lemanaghan appears to have had a close relationship with the nearby prominent monastery of Clonmacnois. While the story does not survive in any medieval hagiography, a legend, recorded in the early twentieth century by a local historian, suggests a folkloric “sibling rivalry” between Sts Ciaran (the founder of Clonmacnois) and Manchan, in the tale of a dispute about the boundaries of the respective territories. This may well have some historical basis. In the early eleventh century, King Maelsechnaill donated several more parcels of land in the parish of Lemanaghan to the community of St. Ciaran, specifically as a payment for rights of royal burial in the Clonmacnois graveyard. Seen in this context, the form of St Manchan’s shrine takes on a new possible resonance, which may help to explain the differences from the earlier tradition of tomb-shaped reliquaries. Instead of a fixed burial site located in a bounded graveyard or at the side of a church, St Manchan’s tomb was moveable. It could travel around the boundaries not only of the church, but of the territory, allowing an extension of the sacred and protected space of the monastic graveyard. Prof. Overbey suggested that the burial space of St Manchan’s Shrine functioned to dilate the boundary of the Clonmacnois graveyard, extending the sacred space to the edges of Clonmacnois’s territory.

Prof. Overbey also suggested that the form of St Manchan’s Shrine, coupled with its historical context, imply a strategic political function for the reliquary. In its fusion of divine protection and political expansion, St Manchan’s Shrine proclaims that it was the destiny of Ua Conchobair, Clonmacnois’ patron in the twelfth century, to occupy the province of Meath forever, and that the saint and the king would be dual guardians of the territory and its people.

The Annals of the Four Masters tells us that, in 1166, “The shrine of Manchan…was covered by Ruaidhri Ua Conchobair, a prime contender for high-kingship of the whole island. Ruaidhri’s bid for military and political dominance in Ireland was contested. So it wouldn’t be unusual for Ruaidhri to become an ecclesiastical patron, enchancing his position with grants and gold. We might therefore view the figures on St Manchan’s shrine as having not religious, but military significance. The figures might represent a particularly valuable type of warrior: one with experience, prowess, and identifiable status. Yet, these warriors are not poised to strike. This symbolic troop may function as a kind of visual reminder, or even visual surrogate, of a military exchange of vassals and soldiers between Ruaidhri and his Connacht and Breffney rivals. St Manchan’s shrine is both the site and visualization of the political contract that allowed these rivals to join forces under the protection and assurance of St Manchan, their co-patron. Prof. Overbey answered questions from the floor. A sampling follows.

Q: What are the figures wearing around their necks?

A: They don’t have anything on their necks. That’s actually the nail pole. Those rings were used for carrying the shrine.

Q: How is Jesus depicted? Is Jesus depicted as a warrior?

A: He wears similar clothing: he wears a loin cloth but he has insized ribs.

Q: Was the touching of relics and bones common?

A: It appears that early on they were readily touchable, but they regularly get stolen and traded. For instance, St Manchan’s is sealed. This starts happening in the tenth century. Viewing crystals appear in the fourteenth century.

Q: Is there a change in making reliquaries after the arrival of the Normans?

A: Unfortunately, we don’t have enough evidence to say. There does appear to be subtle changes in the representation of saints. There are only three or four examples of post-Norman shrines.

Q: Is the bone house in Clare identified?

A: No, I actually had to go and track it down in the Burren.

Q: You say that these figures are mature warriors but they’re not dressed for battle and they’re shirtless. Might they not just be peasants?

A: I guess I’d want to know why they have axes and sticks. This depiction of beard tugging is a common attribute of warriors. It might be just enough to indicate that they are warriors.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Thursday 22 January 2015

Saint Guaire Mór of Aghadowy, January 22

St. Goar, Guarius, or Guaire Mór, of Aghadowy, County of Londonderry. [Probably in the Seventh or Eighth Century.]

In the days of early youth, most probably this holy man had fought his way into the sanctuary of God as a young priest, and had arrived at distinction in the Church. We read in the Martyrology of Donegal, as having been venerated on this day, Guaire Mór, of Achadh Dubhthaigh, now the parish of Aghadowy or Aghadoey, county of Londonderry, on the banks of the Lower Banna, or River Bann. He was the son of Colman, son to Fuactage, son to Ferguss, son to Leogaire, son to Fiachre, son to Colla Uais, who was Monarch of Ireland. He is styled abbot of the foregoing place, in the plain of Li. The Martyrology of Tallaght records him on the 22nd of January, under the simple designation of Guaire. It does not seem probable this saint was the original founder of the monastery at this place, nor does his epithet of Mór, "great," seem equivalent to "elder." He was first cousin, yet removed by a later generation, to the saint, bearing this same name, whose feast occurs on the 9th of this month; and our present Guaire Mór probably succeeded the other in order of time. Perhaps, indeed, notwithstanding such a probability, and his apparently junior age, this Guaire Mór may have founded Aghadowey Church singly, or in conjunction with his cousin; and the term applied to the present saint might indicate superiority, celebrity, or position. Perhaps simply a difference of stature may have caused the distinction in names between Guaire Mór and Guaire Beg.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Wednesday 21 January 2015

Saint Flann of Finglas, January 21

Flann Mac Laich, or Mac Lughdach, Bishop of Finglas, County of Dublin

A considerable share of misunderstanding has prevailed—while even distinguished Irish historians and topographers appear to have fallen into errors —in reference to the special Patron Saint of Finglas. The original name of this village seems to have been derived from the small, rapid, and tortuous "bright stream" that runs through a sort of ravine, beside the present cemetery. Towards the close of the eighth, or in the beginning of the ninth century—as we find in the "Feilire Aengusa" — this place had been denominated Finnghlais-Cainnigh, after some earlier patron, called Cainnigh or Canice. He is generally thought to have been the patron saint of Ossory, as no other one bearing such a name can be found in connection with this spot. Whether or not a monastery had been founded by Cainneach, while under the tuition of Mobhi Clairenech, abbot, of Glasnevin, and who died in 544, can scarcely be determined. It seems probable, at least, that a cell, or monastic institute, had been here erected by St. Canice before the close of the sixth century. Archdall evidently confounds this saint with a Kenicus or Keny, whose feast is assumed to have been on the 12th of October. The life of this saint had been preserved in the church of Finglas. How long after his time the present holy man lived does not appear to be known. However, a monastic institution, and an ancient bishop's see, seem to have distinguished Finglas, in the early part of the eighth century. We read in the Martyrology of Donegal how Flann, bishop, of Finnghlais, had a festival on this day. In the table superadded to this work, the commentator interprets his name Flann, as meaning "red" or "crimson." He is entered in the published Martyrology of Tallaght on the 21st of January, under the designation of Flann mac Lughdach, abbot, of Finnglaise. The Franciscan copy, however, calls him "the son of Laich." The present village of Finglas, near Dublin city, and to the north of it, has the ruins of an ancient—but not its oldest—church, within an enclosed graveyard of very great antiquity. The parish of Finglas is situated partly in the barony of Castleknock and partly in that of Nethercross. Under the head of Finnglais, Duald Mac Firbis enters Flann, bishop, of Finnglais. January the 21st is also set down for his feast.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Tuesday 20 January 2015

Saint Fechin of Fore, January 20

January 20 is the feast of Saint Fechin of Fore. An earlier post on his life, taken from the work of Archdeacon O'Rorke, can be found here. This year we can look at the account of Saint Fechin's life given by Father John Lanigan, as quoted by Father Cogan in his diocesan history of County Meath:

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Sunday 18 January 2015

Inismacsaint

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Thursday 15 January 2015

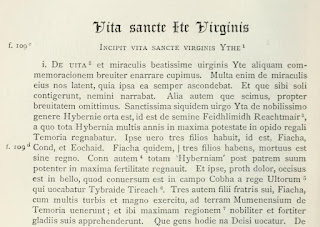

The Teaching and Sanctity of Saint Ite

Some fascinating glimpses of the teachings of Saint Ite and of the sanctity she manifested have been preserved in her Life. Here are a few examples taken from Dorothy Africa's translation of Vita Sanctae Ite from Plummer's Vitae Sanctorum Hiberniae. The Headings are mine.

Saint Ite is transfigured

2. One day the blessed girl Ita was asleep alone in her chamber (cubiculum); and that whole chamber appeared to people to be burning. But when the men approached it to help her, that room was not burned; and all marveled greatly at this, it was said to them from above, what grace of God burned around that comrade of Christ, who was asleep there. And when holy Ita had arisen from sleep, her entire form appeared as if it were angelic. For then she had beauty such as she had neither before or after. So also her aspect appeared then so that her friends could scarcely look at her. And then all recognized what grace of God burned around her. And after a short interval the virgin of God was restored to her own appearance, which was certainly pretty enough.

An Angel appears to Saint Ite and Testifies to the Holy Trinity

3. On another day when the blessed Ita slept, she saw an angel of the Lord coming toward her, and giving her three very precious stones. And when the handmaiden of Christ had arisen from sleep, she did not know what this vision signified. And the blessed (girl) had a question in her heart about this. Then an angel of the Lord came down to her, saying "What are you searching for concerning this vision? Those three very precious stones which you saw given to you, signify the holy trinity that came to you and visited you; that is a visitation of the Father, Christ his Son, and the Holy Spirit. And always in sleep and in vigils, the angels of God and holy visions will come to you. For you are the temple of the Deity, body and soul." And speaking these things, he departed from her.

Saint Ite Struggles against the evil one

5. Not long afterward, the blessed virgin Ita fasted for three days and three nights. But in those days and nights through sleeping and vigils the devil openly (evidenter) fought against the virgin of God in many battles. And the most blessed virgin most wisely opposed him in all, as much sleeping as waking. On the second (posteriori) night, then, the devil appeared sad and wailing, and at day break, he departed from the familiar of God, saying in a grieving tone, "Alas, Ita, not only will you free yourself from me, but many others to boot."

7. And while the blessed Ita was on her way, behold, many demons came against her along the road, and began to contend (litigare) cruelly against her. Then angels of God from above arrived, and fought very hard with the demons for the bride of Christ. And when the demons had been conquered by the angels of God, they fled away through the byways, crying out and saying: "Alas for us, for from this day we will not be able to contend against this virgin. And we wished today to put our claim on her for our injuries; and the angels of God have freed her from us. For she will root up our habitation from many places and will snatch many from us in this world and from the nether regions." But the virgin of the Lord, with the consolation of the angels of God, meanwhile advanced to the church; and in it was consecrated by the churchmen at angelic order on the spot, and took the veil of virginity.

Saint Ite's Asceticism

10. The most blessed Ita made great efforts to keep two and three day fasts, and frequently four days. But the angel of the Lord, on a day when she was exhausted by fasting, came to her, and said to her "You afflict your body without measure by these fasts, and you ought not to do so." But the bride of Christ (was) unwilling to ease her burden, (so) the angel said to her "God has given such grace to you, that from this day until your death you shall have the refreshment of celestial food. And you will not have the power not to eat at whatever hour the angel of the lord will come to you, bringing you food." Then the blessed Ita prostrated herself and gave thanks to God, and from that bounty (prandium) the holy Ita gave to others to whom she knew it was worthy to be given. And without any doubt she lived thus until her death on the heavenly allotment administered by the angel.

Saint Ite Demonstrates The Gift of Prophecy

12. God even bestowed upon the holy Ita such great grace in prophecy that she knew whether the sick would survive their illness or die.

Saint Ite Heals the Sick and Raises the Dead

14. Then the most glorious virgin of God returned to her cell. And when the familiar of God was nearing her community, she heard from nearby a great and immense wailing. For three dead nobles were there, who had died on that day; and their friends were wailing and mourning for them. And they, knowing that holy Ita was passing by, came down,and asked the familiar of God in a doleful tone that she might come and pray for their souls at least. Holy Ita then said to them: "That thing more that you wish beyond prayer for their souls, in the name of Christ may it happen for you." They did not know what to make of this speech at that point. The blessed Ita made the statement because she knew, being full of the spirit of prophecy, that it (or she?) in the name of God would revive them from death. Then the holy one went with them to where the dead were, and while praying she marked the prone bodies with the sign of the holy cross; and they arose living at her command. And the bride of Christ asserted (assignavit) that they lived before everyone.

15. In that place there was then a certain paralyzed man in the clutches of a very great illness, and his friends, having beheld the revival of the dead, took him up and brought him to the holy Ita, that she might cure him. For they had no doubt that one who could revive dead men could cure a sick one. Then the familiar of God, observing the great misery of that man, looked to heaven, and said to him: "May God pity you". And as she spoke, the made the sign of the holy cross on him. Most marvelous to say; when the familiar of God marked the hitherto paralyzed man, he stood up whole and unharmed on the spot before all, as if he had never been seized by paralysis. Then the shout of the whole people was lifted to heaven, praising God, and giving thanks tohim, and glorifying his familiar with deserved honor. Afterward, the familiar of God went on with her companions to her cell.

The Teaching of Saint Ite on What is Pleasing to God

22. At one time the holy Brendan (Clonfert) was asking the blessed Ita about the three works which are fully pleasing to God, and the three which are fully displeasing, the servant of God replied: "True belief in God in a pure heart, the simple life with religion, generosity with charity; these three please God fully. However, a mouth vilifying people (detestans homines), and a tenacious love of evil in the heart, confidence in wealth; these three fully displease God. Holy Brendan and all who were there, hearing such a statement, glorified God in his familiar.

The Teaching of Saint Ite to her Nuns on the Holy Trinity

11. One day a certain holy devout virgin came to the holy Ita, and spoke with her about divine precepts. And while they were conversing, that virgin said to the holy Ita: "Tell us in God's name, why you are held in higher esteem by God than the other virgins whom we know to be in the world. For to you sustenance from heaven is given by God; you cure all the feeble with your prayer; you speak of past and future events; everywhere you drive out the demonic, daily God's angels speak with you; you carry on in meditation on and prayer to the holy Trinity without hindrance." Then the holy Ita said to her: "You answered your own question by saying ‘Without hindrance you carry on in prayer to and meditation on the holy Trinity.' For who ever shall have done so, will always have God with him, and if I was such a one from infancy, all these things, as you have said, properly pertain to me." That holy virgin, having heard this speech from the blessed Ita about prayer and meditation on God, departed rejoicing for her cell.

23. A certain holy virgin, wishing to discover in what manner the most holy Ita was living in her most secret place, in which she was accustomed to be free for God alone, went out at a certain hour, in order to see her. She, then reaching there, saw three very bright suns, just as the natural (mundiali) sun lighting up the whole spot and surrounding area. And she was not able to enter out of terror, but at once turned back. The mystery of this portent would be hidden from us, but for the gifts of the holy Trinity, which made everything from nothing, which the most holy Ita assiduously served in body and soul.

The Repose of Saint Ite

36. Afterwards the most blessed patroness Ita was broken by illness; and she undertook to bless and advise her settlement (civitatem), and the clerics and people of Ua Conaill, who had taken her as their patroness. And having been visited by many holy persons of both sexes, amid the choirs of saints, with rejoicing angels in the path of her soul, after the greatest numbers of virtues, in the sight of the holy Trinity, the most glorious virgin Ita passed on most happily 18 days before the Kalends of February. The most blessed body of whom, with many persons having gathered from all around (per circuitum), with many miracles performed, which still have not ceased to be displayed there, most gloriously, after the solemnities of masses, in her monastery which she the very holy Ita, a second Brigit in her merits and morals, established, from the field, was taken (traditum est) to the tomb, reigning with our Lord Jesus Christ, who with God the Father and the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, God in the age of ages. Amen.

http://monasticmatrix.osu.edu/cartularium/life-saint-ita

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Monday 12 January 2015

Saint Sinell, Son of Tighernach, January 12

St. Sinell, Son of Tighernach.

The Martyrology of Donegal mentions, on this day, Sineall, son of Tighernach, son of Alild, belonging to the race of Eoghan, son to Niall. Again, he is entered simply in the Martyrology of Tallagh on the 12th of January, as Sinell. A conjecture has been offered by Colgan, that the present holy man may be the same as Sinell or Senell, Senior, a disciple of St. Patrick. An alternative guess, however, assigns his possible feast to the 12th of November. But as the disciple of St. Patrick, to whom allusion is made, was the son of Findchath, and one of St. Patrick's earliest converts in Leinster, it must appear that Sinell, the son of Tighernach, was altogether a distinct person.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Sunday 11 January 2015

Saint Suibhne of Iona, January 11

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Saturday 10 January 2015

Saint Thomian of Armagh, January 10

St. Thomian (Tomyn, Tomene, or Toimen) Mac-Ronan succeeded in 623. He was the most learned of his countrymen, in an age most fruitful of learned men. The "Martyrology of Donegal " refers his feast to 10th January:10. C. QUARTO IDUS JANUARII 10.TOIMEN, Successor of Patrick, A.D., 660.The "Annals of Ulster" have, A.D. 660, "Tommene, Episcopus Ardmachse, defunctus est." The "Four Masters," at the same year, have, "St. Tomene, son of Ronan, Bishop of Ardmacha, died. " One of the most important ecclesiastical questions that occupied the attention of the early Irish bishops occurred during the pontificate of St. Thomian. The Paschal controversy then agitated the entire island. The Synod of Magh-lene (A. D. 630) in which the Bishops of Leinster and Munster were assembled, under the influence of St. Cummian, decided that the Roman usage should be their guide; and Ven. Bede mentions that, in 635, the Southern Irish, "at the admonition of the bishop of the Apostolic See," had already conformed to the Roman rite. Not so, however, the Northerns. St. Thomian, in order to secure uniformity, addressed, in conjunction with the Northern bishops and abbots, a letter to Pope Severinus, in 640. When their letter reached Rome, the Apostolic See was vacant, and the reply which came was written, as usual in such cases, by the Roman clergy. This fact is an admirable example of the fidelity with which the early Irish Church adhered to the statute of St. Patrick in the "Book of Armagh," that difficult cases should be sent "to the Apostolic See, that is to say, to the chair of the Apostle Peter, which holds the authority of the city of Rome."

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Thursday 8 January 2015

Saint Ercnat, January 8

On January 8 the Irish calendars record the name of a female saint, Ercnat ( Ercnat, Eargnat, Earcnad, Ergnata) known primarily from the hagiography of Saint Patrick. There she is depicted as one of the high-born female converts who receives

the veil from the national apostle himself. Her father, Daire (Darius), is the local chieftain who grants the site of what later becomes the ecclesiastical capital of Armagh to Saint Patrick. Furthermore, Ercnat fulfills a

designated role within the 'household of Saint Patrick', as one of his three embroideresses, according to the list found in the Tripartite Life. The calendar entry in the Martyrology of Oengus records her as 'Ercnat, chosen to the inheritance' while the Martyrology of Donegal reads:

EARGNAT, Virgin, of Dun-da-en in Dal-Araidhe.

Article III. ST. ERGNAT, VIRGIN, OF TAMLACHT, COUNTY OF ARMAGH, AND OF DUNEANE, COUNTY OF ANTRIM [Fifth Century.]...This noble lady flourished in the very dawn of Christianity in our island, and about the year of Christ, 460. The places of her veneration are called Clauin-da-en or Dun-da-en, in the Feevah or wood of Dalaradia, and also in the Church of Tamlacht-bo. The parish of Duneane is situated in the diocese of Connor. Its church was an ancient one, standing within Lisnaclosky townland. We, find in the Martyrology of Donegal, as having a feast on this day, Eargnat, Virgin, of Dun-da-en, in Dal-Araidhe. This holy penitent's acts have been written by Colgan. Her place is now called Duneane, in the county of Antrim. There is a St. Herenat, Virgin, of this same locality, entered at the 30th of October. It appears most probable, they are identical; in which case, this virgin had a double festival in the year. One of the Irish saints introduced to us this day, in the Felire of St. Aengus, is the present St. Ercnait. The etymology of Dun-da-en, contracted to Duneane, has been interpreted to signify "the fort of the two birds." The four towns of Duneane on one of which the Protestant church stands are surrounded by that part of Lord O'Neill's property, known as " the estate of Feevah." From the Irish Apostle's Lives, it would seem, that Ercnata was the daughter of Darius, and that she flourished as a contemporary of St. Patrick. Darius, surnamed Derga, was the son of Finchod, son to Eugene, son to Niell. This latter seems to have been the distinguished founder, from whom the family and territory of Hy-Niellain, near Armagh, derived origin. Colgan thinks the charming and celebrated locality, known as Drumsailech belonged to him, and that afterwards it was made over to the great Irish Apostle, St. Patrick, to found the noble city of Armagh, the Ecclesiastical Metropolis of Ireland. Among the noble ladies, who received the veil from St. Patrick, St. Ercnata or Ergnata is enumerated. Her love of God was earnest and sedulous. Her pure-mindedness and observance of charitable and pious works served to single her out from among other pious women, to make and keep in repair, as also to wash, the sacred vestments. These offices accorded with the tastes and zeal of St. Ergnat, while nothing on her part was left undone to promote that splendour and decency becoming the Divine Mysteries. At these she attended with rapt devotion. But her love for sacred music furnished an opportunity to the enemy of her soul to excite a momentary feeling, which soon developed into a strong temptation. Her admiration for the exquisite voice of St. Benignus, who sang sacred music with great pathos, presented a dangerous occasion of sin. Thus, even the holiest mortals may have reason to fear the unguardedness of a spiritual friendship, contracted through the purest motives. But, the Almighty saves from the blast of temptation those who fondly love Him, and so was the holy virgin Ergnat rescued from a temporal and spiritual death, through the instrumentality of St. Patrick and St. Benignus. Rendered more cautious by her escape from a great danger,and increasing her labours with sole trust in the sustaining grace of God, she bewailed with abundance of tears in after-life the frailty of a short time. As a penitent, she afterwards obtained that Divine aid, which caused her perfectly to regard only the love of God and to despise that towards created beings. Her closing years were rendered illustrious by signs and miracles. About the middle of the fifth century she is thought to have flourished; but the exact year when or place where she died does not appear to have been discovered. She was buried at Tamlachta-Bo. Probably her death took place about the close of the fifth century. Our hagiographers assign two different festivals to honour her. One of these occurred on the 8th of January, and the other on the 30th of October. The first denotes the day of her natalis; the other feast probably marks some particular event during her life, or a translation of her relics after death. In the Lives of the Saints, nothing engages more our human sympathies than a fall from grace and a subsequent return to its Divine Author; while our own trembling hopes of salvation are encouraged, when so many feeble mortals have bravely resisted the assaults of Satan and escaped from his wiles. The remote occasions of guilt are to be dreaded, since the fires of deceitful passion are seldom wholly extinguished. Sometimes transforming himself into an angel of light, the devil designs our destruction the more dangerously, because his approaches are insidious. He does not desire to sound the note of alarm, when his unseen snares are drawn closely around us.

The Martyrology of Donegal gives some further detail on how Ercnat was saved from her inappropriate doomed love, in its entry for the feast of Saint Benen on November 9:

The holy Benen was benign, was devout; he was a virgin without ever defiling his virginity; for when he was psalm-singer at Ard-Macha along with his master, St. Patrick, Earcnat, daughter of Daire, loved him, and she was seized with a disease, so that she died suddenly; and Benen brought consecrated water to her from Patrick, and he shook it upon her, and she arose alive and well, and she loved him spiritually afterwards, and she subsequently went to Patrick and confessed all her sins to him, and she offered her virginity afterwards to God, so that she went to heaven; and the name of God, of Patrick, and of Benen, was magnified through it.

Archbishop John Healy, shares Canon O'Hanlon's relief that Ercnat's love for Benen was transformed from the earthly into the spiritual, commenting:

It is a very touching and romantic story, which has caught the fancy of our poets and chroniclers, and, as the scribe in the Martyrology declares, gave glory to Patrick and to Benen after God: but none the less is the holy maiden's name glorified also, whose young heart was touched by human love, which, in the spirit of God, was purified and elevated to the highest sphere of sinless spiritual love in Christ. It has often happened since.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2022. All rights reserved.

Tuesday 6 January 2015

Irish High Crosses and the Baptism of Christ

To Brian O'Loony, Esq., M.R.I. A., Professor of Irish History and Archaeology in the Catholic. University, the writer is indebted for the following Irish stanza of the Felire of St. Oengus (extracted from the Leabhar Breac, p. 79, Vellum MSS. of the R.I.A.,) with the accompanying English translation. As will be seen no Irish Saint's name has been introduced at this day, on which the great Festival of the Epiphany or Manifestation of Our Lord to the Gentiles takes place. It is most interesting to learn from this valuable old Irish Hymnology, that our forefathers in the Faith seem to have had a tradition that Our Divine Redeemer had been baptized by St. John on the 6th day of January. The Julian mentioned must be Julius the Martyr, who is commemorated on this day in the MS. Martyrology of St. Jerome. See " Acta Sanctorum Januarii." tomus i., p. 324.

F. uiii. id.

“To his noble chosen king went forth

Julian of abounding purity

Tis not meet to asperse the perfect joy

Of the baptism of the great son of Mary.”

O'Hanlon's clerical contemporary, John Healy, an Anglican rector in County Meath, contributed a most interesting paper on the depiction of The Baptism of Christ on the high crosses of Kells and Monasterboice to The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1893. I have reproduced the first of his illustrations above, but for the others and for the footnotes to the paper please consult the original volume. I have no idea to what extent Healy's conclusions are still upheld by archaeologists today, but he feels that the Kells representation is directly influenced by Byzantine art, which I am sure will be of interest to Orthodox readers.

"THE BAPTISM OF OUR LORD," AS REPRESENTED AT KELLS AND MONASTERBOICE.

BY REV. J. HEALY, LL.D., HON. LOCAL SECRETARY, N. MEATH.

...The Baptism of Our Lord is not a favourite subject in very early Christian art. Rarely once or twice at the most is it represented in the Roman catacombs. It is completely absent from our Irish illuminated manuscripts. I cannot remember it in connexion with any of our Irish metal work, and I am not aware of any Irish representation in stone beyond the two which I am now about to bring under your notice.

The first representation to which I wish to direct attention is that found on the shaft of a cross, which stands in the churchyard of Kells. It is in such excellent preservation that some very minute details may be easily recognised. Here we may notice the river issuing from its two sources, the Jor and the Dan; the Dove descends, not on the Head of our Saviour, but on the river ; Saint John the Baptist stands in the river, but is fully clothed, has a book in one hand and pours water from a kind of ladle with the other. It will be observed that the Baptism, although represented as taking place in the river, is by aspersion not by immersion. The figure of our Lord appears to be nude, and on the bank are the two disciples, whose dress is well worthy of notice as a study in the ecclesiastical vestments of the day. Somewhat similar vestments are represented on the other crosses in Kells as worn by bishops, but they are completely different from the bishop's dress as represented on the Cross of Tuam. Three garments seem to be depicted the outermost, in the form of a cloak, being fastened with a brooch of that ring shape of which so many examples are found in all our museums.

Now it is evident that when this sculpture was executed the curious etymology was known in Ireland by which the name Jordan was derived from the two streams Jor and Dan, which are supposed to unite and form in name as well as in reality the one river, Jordan. The early commentators on Scripture, it may be remarked in passing, spoke for the most part Greek or Latin, and Hebrew etymologies were not with them a very strong point.

Another peculiarity worthy of notice is the nudity of the figure of our Lord. In early times the rule was often observed that those who were to be baptized should be nude, and this rule was followed even when a font was used for the baptism. In all the early representations of our Lord's Baptism the figure is so represented. It is remarkable, however, that the Sacrament is administered by pouring water on the head not by immersion. In J. Romilly Allen's recent work on "Early Christian Symbolism in Great Britain and Ireland" there are several representations of the Baptism taken from Runic fonts. In every case, however, the rite is represented as being administered by immersion.

We have, therefore, in this a fundamental difference between the Irish and the Runic representations. On the other hand, in a catacomb fresco lately recovered by De Rossi and copied from him by Lundy in his work on "Monumental Christianity," baptism is represented as being administered to a nude figure standing in the river, but the method employed is that of pouring water on the head. In other respects the catacomb painting has not much resemblance to the Irish sculpture, so that although this comparison leads us to conclude that the Roman artist and the Irish had the same ideas as to the facts to be represented, we are also led to conclude that this agreement was theological rather than artistic. The teaching was the same, but the conventional representation of it was different. It has been held by many that immersion was the method employed by the ancient Irish Church in baptism, the principal reason adduced being the great size of some ancient fonts. The sculpture we are now considering does not, it is true, decide the question, but as far as its testimony goes it favours aspersion rather than immersion.

The conclusions we have arrived at so far are important, but they are negative. We can see that the artist of the Kells cross had not the same ideas as to the incidents of the scene to be presented, as had the sculptor of the Runic fonts, and we can see, too, that they drew their artistic inspiration from different sources. On the other hand, the Irish sculptor agreed as to the incidents to be represented, but had no artistic connexion with the painter of the catacombs. Happily we can go a step further, and this time in a positive direction. We can trace the source whence this Irish design has been derived, for we have in fact practically the same design repeated in several of the Byzantine and Italian ivories. In the museum at South Kensington, for example, are three panels of a casket in carved ivory, of the Byzantine school. The subjects represented are all scenes from the life of our Lord. They are interesting to Irish archaeologists in other ways besides that on account of which I now direct attention to them. For example, on one of them is represented a church at one end of which are two round towers which seem to be identically the same as those of our own country. Miss Stokes in her work on " Early Christian Architecture in Ireland " gives a picture of the church and two round towers of Deerness. This Byzantine ivory might be taken as a picture of the very same building. On another panel of the same casket we have the Baptism of our Lord represented, and in such a way as to suggest that the artist had learnt in the same school as did the sculptor of Kells. The partially unclothed figure of the Baptist, and the fact of only one source of the river being represented, speak of a more modern date; but notwithstanding these differences, the general treatment and style is the same. The ivory is said to be of the eleventh century. Here then we have a proof tangible and visible that those Greek artists whose influence was being felt all through Western Europe, extended that influence as far as Ireland ; and the question, whence did the Irish artist obtain his inspiration is, as far as this sculpture is concerned, satisfactorily answered. He followed a Byzantine model.

We now come to look at another representation of the same subject, found at Monasterboice. Unfortunately, the sculpture here is much more weather-worn than at Kells; the details, therefore, are not made out so easily. We can see enough, however, to recognise that the two pictures belong to an entirely different school. Our Lord here stands in the river, the water of which reaches to the waist, whereas in Kells it reached only to the ankles. The side at which Saint John the Baptist stands is very indistinct, but the high position of the figure sufficiently indicates that he is standing on the bank, not in the river, as at Kells. There is no appearance of pouring water on the head; indeed, the mode of baptism seems to be by immersion. The Dove descends upon the Saviour's head, not upon the river. The Lord is represented in the attitude of prayer. In all these respects it resembles the Runic designs to which I have already directed attention. An entirely new feature common in ancient art, but one for which there is no warrant in the account which the Evangelists give is also introduced. There is an attendant angel who holds our Lord's tunic ; this again being not uncommon in Runic representations.

We can trace this design still further, and find in Continental models the original from which both it and the Runic examples have been copied. Bosio has reproduced a picture taken from a catacomb fresco which is in all essentials the same as that which we have now under consideration. In it we have Saint John the Baptist standing on the bank, while our Lord is partially immersed in the river; we have the Dove descending on the Saviour's head, and the angel holding the tunic. Still more nearly approaching the Irish sculpture, and again embodying all these peculiarities, are the ivory carvings, especially those of the Byzantine School, several of which may be seen in the Dublin Museum. See specially Nos. 450, 461, 472, and 735. One of these, taken from the front cover of the Sacramentaire de Metz, is here reproduced. It will be seen that in the elevated position of the Baptist, in the figure of our Lord being partially immersed, and in the presence of an angel holding the tunic, it agrees with the sculpture on the cross at Monasterboice.

It will thus be seen that we have two essentially different modes of treating this same event. "What explanation can be given of this difference? I think that a careful statement of the facts of the case supplies the answer. The sculpture at Kells is like some examples that exist on the Continent, but it is utterly unlike any that are to be found in England. Hence it tells us of a direct influence exerted by the Byzantine Masters on Irish art. The sculpture at Monasterboice is also like some Continental examples, but it follows the same design as was adopted by sculptors in England. Here I conclude that the design was only indirectly copied from the original, and that the artistic influence of which it is the expression reached Ireland through Britain. From its position Monasterboice would be a place where British influence would be felt, perhaps, more than anywhere else in Ireland. Not only is it near the coast, but it is also not far from the River Boyne, which was one of the best known approaches to the interior of the country ; and, if I am not mistaken, this is not the only token we have of Saxon, or, perhaps, rather of Scandinavian influence. Where, except at Monasterboice, do we see the figures all decorated with luxuriant mustachios ? Well, in Kells, on the street cross, we have one such figure ; but as the individual so decorated is also represented with horns and a tail, we can scarcely think that the distinction is meant to be complimentary. In Monasterboice, however, the saints all wear mustachios ; and in England you have the same. The font at Castle Froome, Herefordshire, as figured in Mr. Allen's book, looks as if it were simply a panel from Monasterboice.

Many other reflections might be made, but I trust I have said enough not only to explain the two sculptures of which my Paper particularly treats, but also to draw attention to the importance of the study of our stone crosses, and to enlist some workers in a field which will require much labour and many labourers before that knowledge is gained which will enable us rightly to understand the subject.

JRSAI Volume 23 (1893), 1-6.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.